The play was written in Paris in the spring of 1967 when M.L.P. was there with a scholarship from the French government, and it was her personal resistance and protest against the dictatorship regime that had just struck. The author wanted to paint a picture of Creon as a Tyrant who cannot stand today and collapses, not because of the devastation of the Hubris he committed, but because he was an insignificant "little man", conventional and demystified. Thus, the play could only exist through the experience of the Impossible. Antigone being refuted was on a desperate, lonely road. The play expresses the impossibility of the tragedy which is, I believe, another aspect of the tragic, the one that the modern man is living in a world of denial and despair, faceless and alone.

Introduced by Professor of Drama Rhoda Kaufman, the work Antigone or the Nostalgia of Tragedy was presented at Hayward State University, California, under the direction of Edgardo De La Cruz, Directing Professor, and translated by Minoas Pothos in February 1996. The staging of the play was accompanied by Seminars and lectures by M.L.P. to students and the public. In addition to the performance, a "Greek Culture" week was organized.

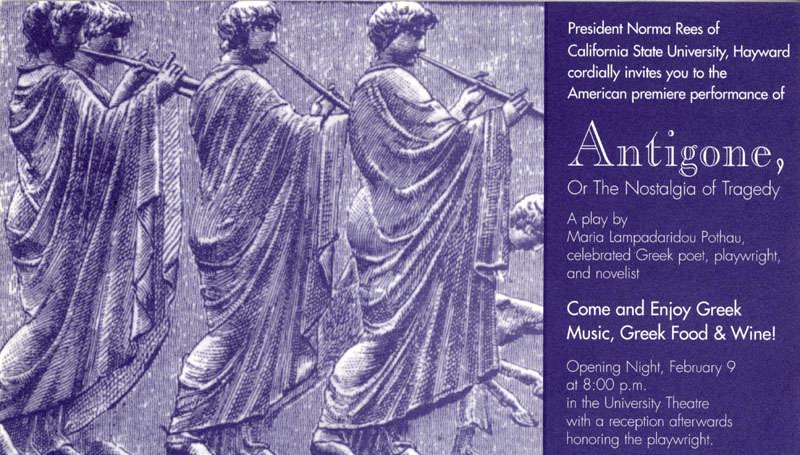

Program of the Antigone performance in Hayward University

Introduced by Professor of Drama Rhoda Kaufman, the work Antigone or the Nostalgia of Tragedy was presented at Hayward State University, California, under the direction of Edgardo De La Cruz, Directing Professor, and translated by Minoas Pothos in February 1996. The staging of the play was accompanied by Seminars and lectures by M.L.P. to students and the public. In addition to the performance, a "Greek Culture" week was organized. Previously, in 1971, Antigone was translated into Flemish and directed by Berten De Bells, at the theater Kelderteater Malpertuis in Flemish Belgium. It was also featured on ERT Radio in November 1980 with Maya Luberopoulou in the title role. In June 1996, the theater department of the University of Athens presented part of the play in a performance entitled "After the Myth". Excerpts of the work were presented in Sweden in March 1996 at Kristofferskan, Stockholm, with a translation by Ingemar Rhedin and with masks designed by Lisa Kjellgren.

Introductory note of 1967

I would like to call this play Nostalgia of Tragedy, set in a time when tragedy has lost all meaning and grandeur given to it by Hubris and Transcendence, this power of struggling with destiny, an era demystified. And that which remained "tragic" is precisely the most incapable and impossible of being expressed tragically. But this very "inability" of individuals to live through a tragedy can, in fact, be the most tragic form of a pitifully lost consciousness of another time and space. The loss of consciousness of the myth archetypes. I still think that the very absence of all those tragic elements that gave beauty to people, at a time when nothing could save them, could be the most tragic fate of our time. That's the idea I want to put across with Antigone. People, unable to be tragic in our time, they meet their own "tragic fate", just when they realize how poor, naked, pitiful they are. Little Antigone longs to be "beautiful and grand" tonight. The beauty and grandeur that only action and consciousness give tragically. "Who knows if I can do it!" She says at first, still drunk by the smell of earth, where she will dig with her hands to bury her beloved dead, and the vertigo of the sacrifice. Without even knowing what an "ugly" death awaits her. Refuted by what she thought was beautiful and grand, she would suddenly feel lonely, small, weak. And she is unable to admit that these pathetic faces around her are all that is left from stripping away the truth - from the demystification of our own times - that she will keep her course, however proud. With that pride of victors. "To die of ugliness, because you can't turn what you love into something beautiful ... It's horrible, horrible ..." she will say at the end. And yet, in her denial, in her stubbornness, and in her beautiful drunkenness, is where all the pulse and all the nostalgia, all the passion and the thirst for a truly grand and beautiful tragic Antigone is hidden.

Paris, Spring 1967

Speech for the International Woman’s Playwright Conference, in Athens

Συνέντευξη στην Έλενα Χουζούρη, το 1973, μετά το Παρίσι

Reviews

In his letter, theatrologist and writer Bernard Dort mentions the following about the play:

(…) I very much love this Antigone. It is a piece of work that is mature and steady. I particularly love the expression, which is simple and dense. This is really where your voice can be discerned, beyond reflections and influences. This Antigone causes a deep emotion. This is a true theatrical play and not a study in theatrical art.

(...) I moreover find particularly interesting the central idea: This is an Antigone for whom they deny the potential of being tragic and at the same time they discover in her the tragic Antigone. This appears to me a variation very modern and very exact on the topic. It attests with certainty a true theatrical writer.

Edgardo De La Cruz, professor of theater arts at California State University Hayward:

It is an honor to direct a play such as this. Its creation tested the limits of our abilities to match the poetic images and intensities of the text, to find the theatrical equivalents that would create vital and surprising experiences for you, the audience.

(...) I felt that in the play there were powerful surges of passion and I wanted to uncover them and to find poetic three-dimensional images to reflect them so that the audience could participate in the heroine’s attempts to define herself.

It is very rare these days to find plays that deal with archetypes. Maria’s characters were archetypes, even icons of universal personalities. This production pays homage to all the wonderful aspirations of humanity for a braver more meaningful world.

(From the play's programm, Feb. 1996)

Rhoda Kaufman professor of dramatic literature and history at California State University Hayward:

In Sophocles’ play, Creon, who is then King of Thebes, gives an order that the corpse of Antigone’s brother, Polyneices, should remain unburied, to be devoured by dogs and birds of prey. At the time, it was high impiety to leave him unburied. Antigone, obeying the law of conscience, buried her beloved brother, knowing that the price she would have to pay for her act was death. For Ms. Lampadaridou Pothou, Sophocles’ Antigone was the ideal of human dignity and of resistance against an unjust law. Antigone had the strength to reject this law, rejecting the tyrant himself at the same time. Her death, the price of her action, would give her the grandeur of a tragic heroine.

(...) Thus Ms. Lampadaridou Pothou wanted with her play to show the irrational nature of contemporary tyranny, to depict a people’s Chorus that was self-aware, and ready to reject absurd nuhorities based on irrational power.

(...) This contemporary Antigone of Maria Lampadaridou Pothou is intoxicated by death and the legacy of her own destiny as a tragic heroine. In her world, however, the gods are tired, and the royal palace is a mass of ruins. Creon is an old, avuncular figure, not rigid, but willing to compromise.

Read the full text from A woman of Lemnos

Archives