CHAPTER ONE

To Lemnos, The Isle Beloved

The sign

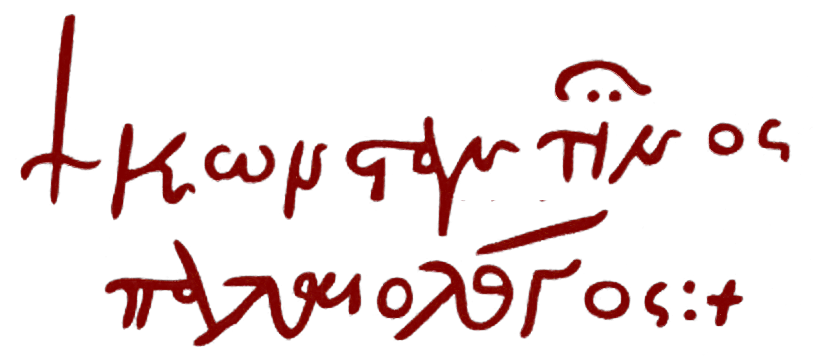

On the day of my birth there was no sunrise. Dark mournful clouds covered the sun, and on my forehead there was a round birthmark, an ochre spot, which everyone said was the sign that I was blessed at birth to become the witness of blood. They said, too, that I was the male child worthy of receiving the heirlooms that had lain in the linen-chest from one generation to the next for five hundred years. My mother, Rhodo, with the golden visage and the fragrance of roses in her white body, nursed me, and they said that when her lips touched the birthmark on my forehead, she saw there an ochre glow forming a circle around the sign that generation after generation had waited five hundred years to see. And she wept. It was the 29th of May 1430. In the village of Hagios Alexandros on Lemnos. Whenever I think of my mother, may God rest her soul, a fragrance of burnt rose trickles into my spirit, a fragrance purified by sacrifice and mourning, just as I experienced it years later in the Hagia Sophia and in the Convent of Christ, at that hour when blood flowed in torrents and wailing rent the foundations of the universe. It was as if that fragrance became one with the blood of the Imperial City, because it was the fragrance of soul and of sacrifice. In these bleak hours, as I sit all alone in my ascetic hermitage of silence to record my memories of the disaster, I know that the soul of my mother, Rhodo, the rose-flower, is here beside me, at a distance of peace from my hand, at a distance of liberating death. I mean that the fragrance of her soul keeps me company. It is nearby as I recount my memories of the calamity, I, who experienced, minute by minute, courage and death, the ultimate agony, by the side of Constantine Dragases Palaeologos, my beloved Basileus of the invincible soul, by the side of Ioannis Giustiniani, the black archangel, I, who was deemed worthy to be the witness of blood and ruins. I must hand over the manuscript to my son, Constantine, before it is too late. He is the one who will enter The City as liberator, because he was born of her blood and her lamentation, and because he is Constantine, the son of Eleni, and bears the mark of grace, according to the letter of the prophecy.

The years of innocence

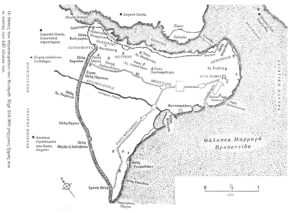

I was twelve years old when by the grace of God I met Constantine Dragases, son of Manuel Palaeologos, who was Emperor of the struggling Imperial City before John VIII. I met him in my homeland, Lemnos, the day he buried his wife Catherine. It was in August of 1442. In those days, at Kotzinos, where the mighty Venetian fortress with its eighteen towers still stands, they excavated Lemnian Earth, the famous terra sigillata. From that blood-red earth they manufactured therapeutic tablets stamped “Terra Lemna,” which were sold at very high prices to wealthy aristocrats or given away to the poor, as a cure for fevers and bites. Galleys with carved wooden prows and gold-embroidered pennons arrived from East and West in the renowned port of Bournia, to take on loads of the famous Lemnian Earth. That year my father, Theodosios Sgouromallis, from Hagios Alexandros on Lemnos, may God rest his soul, took me with him to the festival of the excavation at Kotzinos. I was then a tall, slim lad with dried tears on my cheeks. My mother, Rhodo, whom I adored, had died a few days before, and the little education my godfather, Panayiotis Kikezos – may the merciful God rest his soul – had given me made me pensive and uneasy. How I remember that tall, thin, solitary boy with the large sad eyes, who still lived in innocence and dreamed of the impossible! Today, twenty-eight years later, I know that innocence is not affected by the span of tears. Then, I was living in that pure white expanse, walking barefoot and alone to meet my destiny. Sometimes I think he is still inside me, that barefoot child, silent, watching me, like a mythical extension of my much-tormented life. Or, again, perhaps that child has become one with my only son, who will enter The City as conqueror with all the saints and with the banner of the Resurrection, because it is ordained in the scriptures and nothing can stand in his way. He is the son of my Eleni, who was wounded by the infidels at the Convent of Christ, where she fled with the child to seek refuge, on that black, pitch-dark day of ruin. Others said she lost her mind and calls my name at night. And I climb to the top of the barren hill and hear her voice. For seventeen years I wandered through ruined monasteries in unfriendly places, places conquered by the Turks, searching for her, but in vain – may the all-merciful God have mercy on her if she is still living. πam wearing a darkish homespun tunic, fastened with a long knotted cord around the waist and I am twelve years old. In the milling crowd at Kotzinos, my father is holding my hand, so as not to lose me. The death of my mother has bound us together, it seems, and has brought us closer to each other. “I am now mother and father for you; you will want for nothing,” he had said to me a few days earlier, his voice full of affection, as when he talked to our animals. Then he took the heirlooms out of the linen-chest and brought them to me. She had instructed him to give them to me immediately after her death, to make me a man, she said, to go to meet my destiny. They were wrapped in an old red fabric interwoven with gold that smelled of linen-chest and time, together with a timeworn parchment that was frayed at the edges. I was the blessed one, they said, the one deemed worthy to receive them, but what that meant I did not know. Sometimes, I would gaze at the mark on my forehead in dim mirrors or in clear waters, that mark of ochre light, not knowing yet that later it was to become my cross and my martyrdom, in the tortured years beside Constantine Dragases Palaeologos, my ill-fated Basileus. I was sitting by the stone threshold of our house in Hagios Alexandros on Lemnos on the day we buried my mother, struggling to understand the meaning of death on such a brilliant day, as waves of golden sunlight flooded my face. I remember even now the agonizing thought of that golden afternoon, that during the coming night, I had to become a man, and I went away, I remember, up to the cave of Philoctetes, to the deserted ruins of the Cabeirion. I needed to feel pain, not knowing yet how harsh, how fierce that first pain was to be. I began to shout, to bellow, Mothe-e-e-r, to roll on the earth redolent with its herbs and its medicinal plants that healed the wound of Philoctetes, and the tears flooded my cries, MOTH-E-E-E-R. πt was then that I sensed the fragrance for the first time. Dawn was breaking and I was still there, among the ruins of the Cabeirion. When I looked up to see the first rays of the sun that refracted a rosy emerald light, I shuddered to the depths of my being. Her fragrance, that peculiar scent that emanated from her body or her soul was there, and I knew that she herself was there, unseen, and I ran madly this way and that, my arms outstretched with longing, you are here, close to me, give me a sign, I said to her, give me a sign, Mother, Mother... In the dusk I saw her form coming toward me, calm, ethereal, a luminous form, soul or shadow, Mother, don’t be afraid, my son, she said, don’t be afraid of anything, I am near you, and it was her voice, that sweetest voice in the world. I knew from that moment on, learned it in my twelfth year, that the invisible world, the world of shadows and souls, is more solid and more real than this world of uncertainty and doubt – that other unknown world, which held the greater part of myself, the most innocent and tender. That world with the fragrance of burnt rose rises up through the fissures of my soul, bringing with it entire pieces of my past life, and then I know that Mother is beside me and I am calm. When I returned home, Father was waiting for me at the door. I said nothing and he understood. He raised his hand and touched the dried tears on my face. Then he unwrapped the purple cloth and took out the heirlooms with great care, as if they were sacred, “These are for you,” he said. I looked at them and was blinded by a dense light. A curious brilliance kept me from seeing them. Perhaps Father did not see the brilliance, for he continued calmly, “This small icon of the Virgin is the work of St. Athanasios of Athos, a prophet, the founder of Hagia Lavra, who, five hundred years ago, gave it to one of our ancestors, Theodosios Sgouromallis from Hagios Alexandros on Lemnos; it is his name, they say, that we bear.” Father was talking and I was still looking at the tiny icon that gave off a brilliant light and was almost transparent with age. Slowly, the dense light subsided and I was able to see it. I stretched out my hand to touch it and shuddered. The light it gave off was alive. Father recounted the story of the five hundred years, of the male child who was to be born with the sign, the ochre circle in the middle of his forehead, between his eyes, and how it was to this child that the heirlooms should be given, because it was so written in the parchment. “Now you know why your name is Porphyrios,*” he added, moved, and hung the small, miraculous icon around my neck. I bent over to look at it. It was blackened now, worn around the edges, and I was not surprised. It transforms itself, I thought, and smiled. It was a wooden ornament of delicate handiwork in the form of a cross, which depicted the Virgin and Child on one side and the Crucifixion on the other. I touched it with my hands; the dense light that had blinded me a little before was not there, nor was the brilliance that made it appear transparent. Yet by a strange intuition I knew that hidden inside it was the power of its brilliance and I squeezed it in my hand. Hidden inside it, the miracle awaited me. I did not speak, and Father did not understand. “Here is the other heirloom,” he said, and showed me three lion’s claws set in tooled leather. Basil, himself, he who was also known as Digenis Akritas, he who bestrode mountains, who wrestled with Charon and defeated him, had presented this talisman to Theodosios Sgouromallis five hundred years ago, “Here, it’s all written down,” he said, and opened the timeworn parchment. It said that Theodosios went to find him, in the lands by the Euphrates, to ask him how he, too, might wrestle with Charon, overcome him, and bring back to life Rhodo, the woman he loved. “Take this, too, as your talisman, my son, take it; you are the blessed one... you were born with the sign of grace.” I took the talisman of Basil, who was called Digenis Akritas, in my hands, and I was awe-struck. Straightway I felt an enormous power, as if I, too, could bestride mountains or wrestle with Charon and overcome him. Digenis has given me his power, I thought quickly, and I placed it around my waist. But its power did not come to my aid; I fought tooth and nail against the Turkish infidel and did not defeat him. Today, I have none of those heirlooms. I gave them to my son, my Constantine, the one who will enter the Imperial City as liberator at the appointed hour. He will defeat the infidel.

The fated encounter

Father’s hand draws me into the crowd. Something noteworthy has happened that I, deep in my own thoughts, did not notice. People are going toward the port of Bournia, where the multicolored galleys await them, and others are going toward sheltered Pterin, but we follow a funeral procession that is going toward Hagiochoma. The bright light dazzles my eyes as the crowd presses around me, and my hand slides slowly out of Father’s palm. I am standing alone now in a shadow, watching. Funeral carriages pass by, officers on white horses, the nobles of the island in formal attire, and the priest, chanting the service for the dead. The landscape appears transparent, as if it was of water, a bluish space where all the cicadas are droning together. Again the thought crossed my mind that this world of psalms and tears is uncertain and unstable, even though it appears stable and strong, while that other world of silence, is sweeter, more loving, more certain, because it holds Mother. I watch the officers in their brilliant uniforms, their swords sheathed in gold decorated with precious stones, and in their midst a tall, handsome warrior who is both noble and valiant, like a demigod. I watch him as he bends down now, bends down toward the earth, falls upon it and weeps.... He weeps. He is Constantine Dragases Palaeologos. At the inn, where we were staying, I learned about him. He was Despot of Mystra. He was on his way, they said, to the Imperial City to assist his brother, the Emperor John, when he was set upon by Turkish galleys and made his stand in the castle of Kotzinos, on Lemnos. With him was his wife Catherine, the daughter of Dorino Gattilusi, the Lord of Lesbos, and she was with child. There, at the inn, I learned his entire sorrowful story, how he had married the first time at the age of twenty-four and was unlucky then, too. His first wife, the lovely daughter of Duke Leonardo Tocco, Magdalena, who later took the name Theodora Paleologina, died in childbirth a year and a half after their marriage, and Constantine, who loved her, they said, mourned her deeply and would not even hear of another marriage. However at the age of thirty-six, his heart was stirred once again, this time by the beautiful and kindly Catherine, and he loved her with a mature and deep love. His secret desire was to have a child – how he longed for a son! None of his brothers had a son and the dynasty was in danger of dying out after him. Alas, on Lemnos he was to lose both wife and child and his suffering was unbearable. “I am unlucky, unlucky,” he was heard to say, “unlucky.” The twenty-seven days of the siege and its hardships exhausted and weakened Catherine, although she tried to hide it. She withered like a flower, wilted and disappeared silently, without any complaint, not wanting to hinder the struggle of the fighting men. Constantine fought bravely, defeated the accursed Ahmet, destroying his low-prowed galleys with the black pennon of the Prophet, but calamity struck from elsewhere, and there, at Hagiochoma on Lemnos, together with his wife and his child, he buried his dear friend, the droungarios Nikolaos Sophos. Nikolaos had fought like a lion beside his lord, but he was mortally wounded on the last day, they said. Like Catherine, he, too, breathed his last on Lemnos, on a warm August morning in 1442, when I, a child, chanced to be there, and his death marked my life. One never knows what that inscrutable element is that arouses our souls and makes us yearn for the impossible. Now, after so many years, as I reflect on it, I say it is the will of God. In our great desire for something, there is always an inscrutable fate that pushes us blindly to do this or that, even though we believe that we have done it out of our own strength or weakness. As I lay down that night on the shabby mattress, there, in the hostelry built of mud-brick, and before sleep closed my eyes, in those sweet moments when we dream, I saw Constantine Dragases alternately weeping and falling to the earth and galloping on a pure white winged horse, so impressed had I been by his noble countenance and his unbearable pain, which was the pain of a valiant man. I did not know, yet, that pain can make the most humble man valiant. Although we were to leave very early on the following day, I arose before dawn, put on my cloak and headed toward Hagiochoma, where they had buried Catherine. Even now, I cannot say what drove me to desire so ardently to see the grave that had pained the demigod. Or, perhaps, I sought to weep there for my own mother, as if it were possible for me, the insignificant one, to unite my pain with his, to find the passage to his valor. Before my eyes was that same image of him alternately falling to the earth to mourn, and galloping on a pure white stallion. In the morning stillness, I could even hear the hoofs of the horse, which shook the foundations of the earth, a vision bathed in the first rays of the sun. I had closed my eyes, surrendered to that superb vision, there, before the bare grave, before the two bare graves, when I heard voices close by. I froze. I thought I had imagined the sound of hoof-beats, then I saw before me three horsemen in white battle-dress, three huge men, one with a noble face shadowed by heavy grief. I recognized him immediately. He was the one I had imagined as a demigod, the one I had seen falling to the earth and weeping. Constantine Dragases Palaeologos. I was confused and started to leave when I saw him approaching. He looked at me with wonder, and then his voice, affectionate: “What are you doing here, child, so early in the morning?” I looked straight into his eyes, as if seeking to communicate to him my thoughts of a few moments before. “I came to the grave,” I answered. That appeared to have made an impression, for he paused beside me and gave me a strange look, one of those looks that never leave the memory, that pierce the soul, mark it. “What is your name?” he asked. “Porphyrios,” I answered, “Porphyrios Sgouromallis.” The ochre mark on my forehead must have glowed in that silent dawn hour, for he put out his hand and touched me there, exactly there. Then, from around his neck, he took a gold cross with four small rubies, like drops of blood, that formed the letter B on each arm, and he gave it to me. “Take it, to remember me by...” he said. And it was as if that hour united us, as if it was an indelible writ of the pain that was to come, a fated encounter. I still wear that precious, beloved cross under my black cassock, a valued and holy relic, sole witness of my past life. Two of the Bs face backward, toward the past of glory and ruins; the other two face forward, toward the ineffaceable future.

Last chapter of the book page 729

My son, my Constantine, my son, my golden eagle

No, I cannot continue. I hear the hoof-beats and say, I have finished my narrative, I place the manuscript in my bag, to hand it over to my Constantine, who is on his way. I put it away quickly, because the hoof-beats are louder and closer and, this time, yes, it is true. I go to the doorway and look out at the road. My heart is trembling, beating wildly, it will burst, I tell myself, because it is my Constantine who is coming, my Constantine is coming. He is dressed in dark clothing, gray or charcoal, black, and he is handsome as an angel on his white horse, no I cannot write anything more about the calamity. I did not have time to talk about the Cretan sailors, who fought on alone until late afternoon, when the Sultan came into The City, or about how our last flag was lowered from the Fort of Alexios near the Horaia Gate. And I wanted also to tell about the terrible night I passed in the sea-tower, among our dead, from where I heard the wailing and the heart-rending cries of the wretched people bound in chains and of others who ran, frantic, toward the ships, begging for passage. From the small embrasure I could see the moon that was disappearing in its impassive orbit, that last moon, whose light was aggrieved by the prophecy that came to pass. But I cannot recount any more about the disaster, because my Constantine is coming now, the son of Eleni. It is he who will be the first to hear the trumpet of the Angel, he who will receive the sword that I was not worthy to receive, from the hand of the Angel. It is he who will enter the Imperial City as its liberator at the appointed hour, as the new prophecy foretells. He, who will go to wake the Basileus who was transformed into marble, to bring him back alive and covered with blood. My Constantine is coming, I see the dust of his horse hooves, just as they were in the silver depths of the mirror. He is coming... He bestrides mountains and gorges, or so it seems to me. His horse does not touch the ground, it dances on air and the flowering fields rise up on tiptoe to watch him. And I tell myself that he could only have come in May, which is the month of the crucifixion and the glorious rebirth, the month of sacrifice and of hosannas. I stand at the door of the cell, a small house, now, and I cannot take even one step, my body is paralyzed. But my Eleni runs. She is able to. She saw him first and runs. Perhaps she, too, heard the hoof-beats or perhaps the wild beating of her heart, and she runs, she can wait no longer. She collapses and falls and gets up again, “I did not hold you to my breast in your fifth year... did not sing to you in your sixth... did not keep watch by your pillow in your seventh... did not see the sadness in your eyes in your tenth... did not take pride in you in your thirteenth...,” and she runs into the silken morning that had saved all its emerald dew and all its fragrance of rebirth for this sublime moment, for this horseman who is coming on his white horse. I am holding the pearl cross in my hand. It is what united us, I tell myself. It is what will complete the circle of time, like a precious ring with a pearl on your heart, Imperial City. He knew that he would find me here, on the hilltop, he knew. And he gallops, gallops like the wind and like the upright, golden wave; he gallops, scattering wreaths of sparks on the crystal of the morning in his passing. The road grows shorter, he is here, I tell myself, and there, he is dismounting, sees his mother, they are embracing and both are weeping now. Soon, in two moments, one... an archangel with amber eyes like mine, long ago, and he sees me, smiles, surely he recognizes me. The mark on his forehead must be glowing, like mine, that, that is what brings him to me, I tell myself, the sign. An archangel, yes, and the light of seven suns shines on his face, two moments more, one, half, my hands tremble and my body is collapsing, I cannot hold it up, a little longer my God, a little longer, my Constantine is coming, a little longer, and the tears dull my vision, ah what sweet tears awaited me, what a sweet death... A little longer... my breast aches, and I hold out my arms now, hold them out wide to clutch him to my breast. My Constantine is coming... My Constantine is here! My son, my Constantine... My son, my golden eagle!